At the Táo IWSS (International Wine & Spirits Show), 17-20 March, Shangri-La, Chengdu, China 2019

Text & Photo © CM Cordeiro 2019

The 2019 Táo IWSS (International Wine & Spirits Show) took place from 17-20 March in Chengdu, China. It was a 4-day trade-only event of the 100th CFDF (China Food and Drinks Fair), where exhibitors move from showcasing at hotels to the Chengdu Western China International Expo City from 21-23 March. In 2018, Táo IWSS had 15 pavilions between the Kempinski hotel and the Shangri-La hotel housing exhibitors from both renowned and emerging wine-producing countries and regions, including China. Record trade visitors were documented in 2018 with over 550 international and domestic exhibitors at the Kempinski hotel, and over 600 exhibitors in Shangri-La hotel. There were over 80,000 trade buyers from China alone to the Táo IWSS in 2018.

The atmosphere at the Shangri-La hotel for the Táo IWSS 2019 was competitive and intense. The mid-morning scene at the Táo IWSS 2019 Shangri-La exhibition saw taxis and private hire cars pull into and out of the hotel driveway as a stream of vehicles on a conveyor belt, letting people into the trading area in steady jiggers. There was little time for leisurely browses through the myriad of wine bottles on display. Rather, the observation was that buyers seemed to know what they were after, and focused solely on that acquisition process. Events such as wine tasting, and new product launches were also part of the exhibition.

A thematic focus for the Táo IWSS 2019 at Shangri-La hotel in Chengdu when speaking with traders was the bolstering role technology played in the processes of wine traceability. The adulteration of wine began since its very production in ancient Rome. Nobility in Rome could never be assured that the wine they were consuming at the table was genuine, and for the poor to middle class of Rome, there seemed an abundant supply of prestigious wines to be acquired and consumed at unusually low prices at their local eateries [1]. Romans in Pliny the Elder’s time considered the treatment of wine with smoke an effective means of making the wine seem old. Pliny’s lament of the extent of wine adulteration in ancient Rome is renowned and well-cited:

“Today indeed not even our nobility ever enjoys wines that are genuine. So low has our commercial honesty sunk that only the names of the vintages are sold, the wines being adulterated as soon as they are poured into the vats. Accordingly, strange indeed as the remark may seem, the more common a wine is today, the freer it is from impurities” [1:581]

Pliny’s remark on common wines seems as relevant today as was from his time. From ancient Rome to modern-day China, according to Maureen Downey, a wine expert from Chai Consulting in a Forbes interview in 2017, as much as 50% of the more valuable wines in China are believed to be counterfeited, with a market value of 3 billion USD [2,3]. Still, technology has certainly advanced considerably in the past two decades, even if counterfeiting techniques too become increasingly sophisticated [3]. What measures were wine producers and traders taking in ensuring product authenticity towards concerned consumers? In the context of Industry 4.0 and digitalisation, do they use any advanced packaging or labelling technologies for their wine bottles to ensure authenticity and traceability?

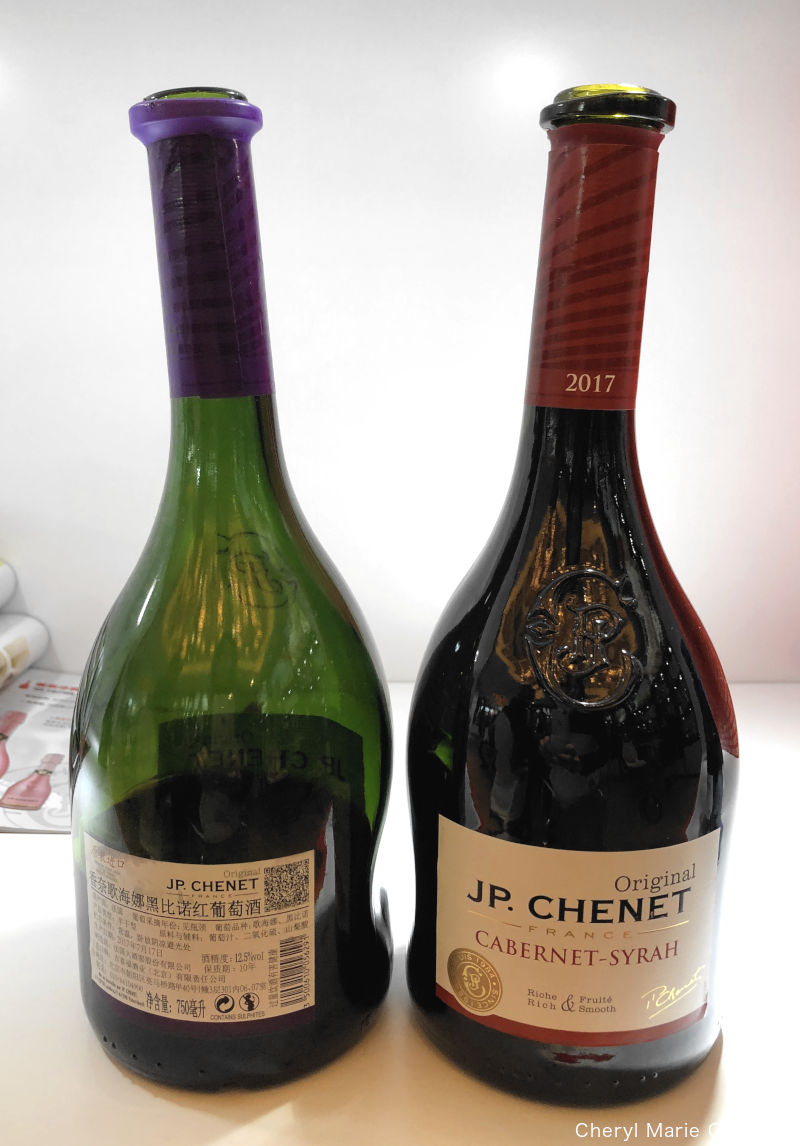

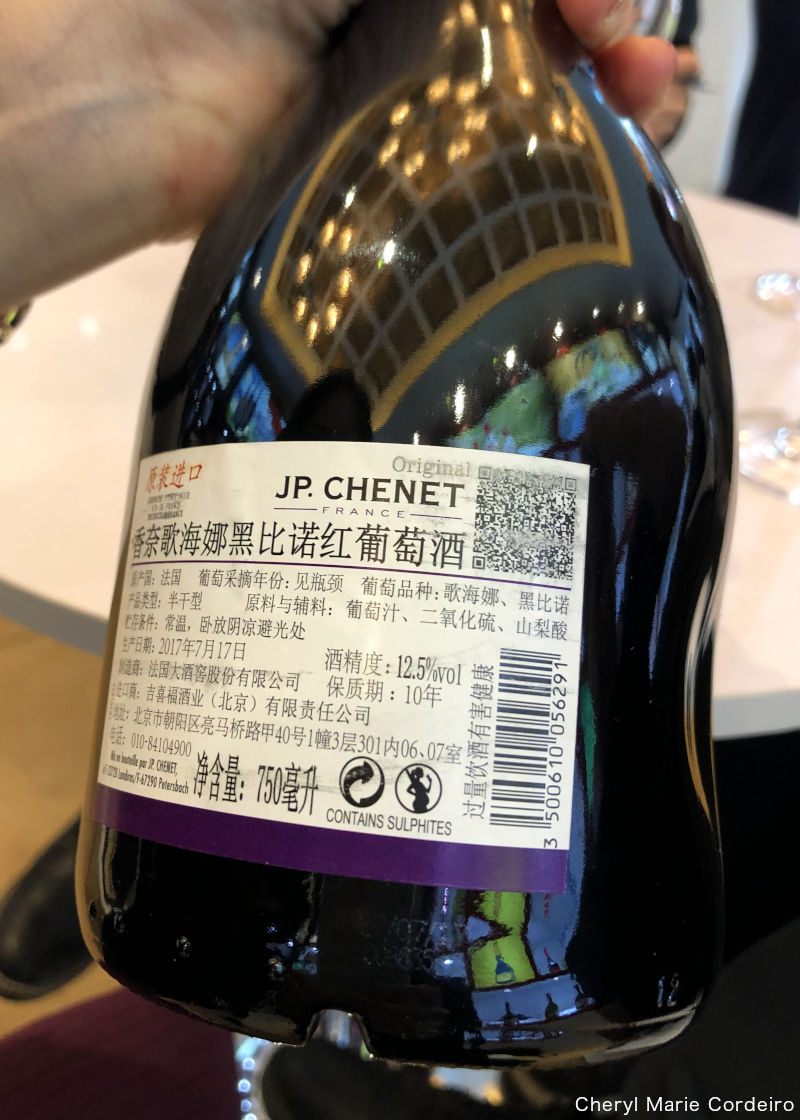

My questions brought me to the topic of intelligent packaging technologies combined with packaging aesthetics [4]. There are a combination of techniques applied in ensuring product authenticity that included sales tracking in secondary markets, labelling technology (including holographic labelling), human policing, vintage dated corks and bottle identification numbering [5-8]. Blockchain technology is currently being invested in, but awaits effective global value chain implementation [9]. At one exhbition booth, some JP. Chenet bottles (pictured below) were shown. Features of importance and observation points for end-market consumers are the shape of the bottle, the weight of the glass, the capsule that covers the tops of bottles and the depth of the punt (the indent at the bottom of the bottle). These JP. Chenet bottles also employed a multi-layering of labels, a feature meant to discourage counterfeiting.

Most traders spoken with indicated that they did not however, expect intelligent packaging that employed advanced technologies to eradicate entirely the counterfeit trade. Rather, most acknowledged that China’s wine market is in itself evolving, with the wisening of consumers. The consumer market for red wines in China is fairly nuanced and segmented. According to traders, concerned consumers in China will only buy French and imported wines from trusted sources, or sources that their trusted sources would recommend. The Chinese government’s efforts in raising consumer awareness for food authenticity in general has also helped in the shift towards more informed consumption of wines in China.

Where Bordeaux wines dominated the market just about a decade ago, today, red wines are appreciated from new world regions such as Chile, Australia and South Africa. While intelligent packaging technologies certainly bolster the processes of wine traceability and authenticity, the opening up of China’s wine market towards new flavours and textures of red wines indicates too, a maturing of palates that in both short and long term business cycles, has the potential to negatively impact the counterfeit wine trade.

A wine trader, explaining the idea behind their bottle design that helped their customers identify an authentic JP Chenet.

References

[1] Bush, James F. (2002). “By Hercules! The more common the wine, the more wholesome!” Science and the adulteration of food and other natural products in ancient Rome. Food and Drug Law Journal, 57(3), 573-602.

[2] Lee, J.C. (2017). How to avoid buying fake wine, Forbes. Internet resource at http://bit.do/forbes012017wine. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

[3] Lee, J.C (2017). Fake wines is a billion dollar market and here are the ways to identify them, Forbes. Internet resource at http://bit.do/forbes2017wine. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

[4] Sohail, M., Sun, D., & Zhu, Z. (2018). Recent developments in intelligent packaging for enhancing food quality and safety. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 58(15), 2650-2662.

[5] Gittleson, K. (2014). Wine fraud: How easy is it to fake a 50-year-old bottle? BBC Business. Internet resource at https://www.bbc.com/news/business-28697721. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

[6] Przyswa, E. (2014). Choosing a Fraud-Prevention System Take a closer look at RFID and NFC technologies for wine anti-counterfeiting, Wine & Vines Analytics, October 2014 Issue. Internet resource at https://winesvinesanalytics.com/features/article/139571/Choosing-a-Fraud-Prevention-System. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

[7] Smale, W. (2017). The wine detective battling counterfeiters, BBC Business. Internet resource at https://www.bbc.com/news/business-39404487. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

[8] Lecat, B., Brouard, J., & Chapuis, C. (2017). Fraud and counterfeit wines in France: An overview and perspectives. British Food Journal, 119(1), 84-104.

[9] Poola, H. (2018). Blockchain wine, Jancis Robinson. Internet resource at https://www.jancisrobinson.com/articles/blockchain-wine. Retrieved 26 March 2019.